In an era of complex political change, the traditional labels of "Left" and "Right" often feel inadequate, if not entirely broken. Voters and ideologies increasingly defy easy categorization. How, for instance, can one model explain both trade-protectionist conservatives and free-market globalists? How does a simple line account for anti-state anarchists and state-centric communists, both of whom are typically labeled "left-wing"?

This widespread confusion is not a failure of public understanding. It is a failure of the model. The single-axis political spectrum, a relic of the 18th century, is no longer a useful map for the 21st-century political world. It is a tool that, through its simplicity, now creates more distortion than clarity.

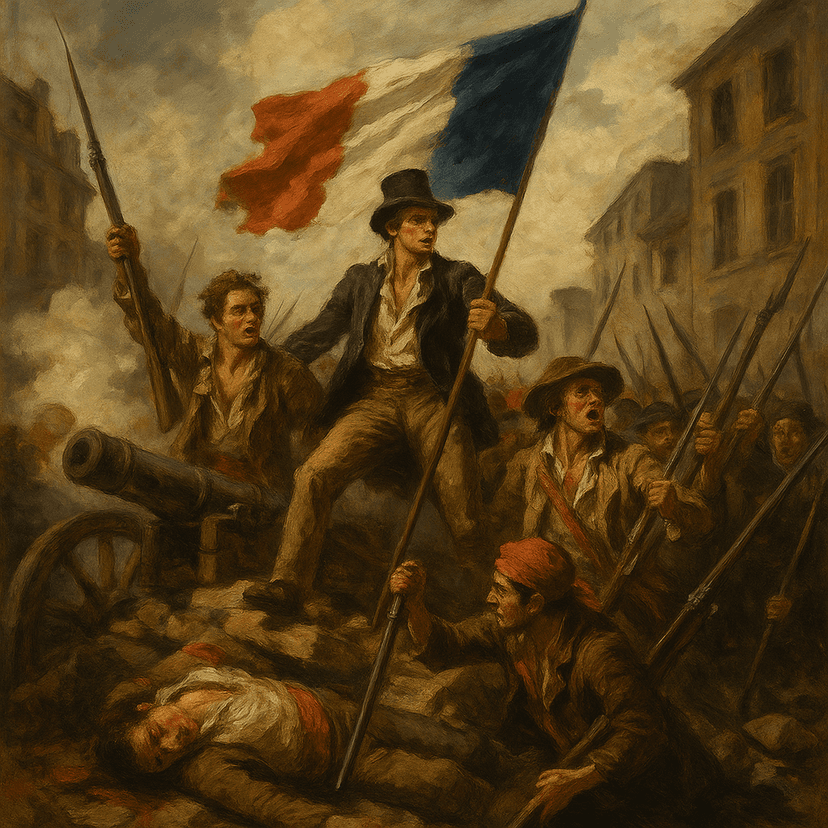

A Historical Accident: The Seating Chart of 1789

The origin of the Left-Right divide is not found in a profound political theory but in a literal seating chart. The terms first appeared during the French Revolution, beginning in 1789.1 When the new National Assembly convened to draft a constitution, a spatial division occurred. Members who were loyal to the Ancien Régime—supporters of the king's authority, the monarchy, and tradition—took to sitting on the president's right side.2

In opposition, those who supported the revolution—who sought to limit the king's power and championed change, republicanism, and popular sovereignty—grouped themselves on the president's left.2 In the context of France, the Left became known as "the party of movement," while the Right was "the party of order".3

This simple division, born of convenience, became a persistent metaphor for political conflict.

The Malleable Metaphor

Crucially, the meaning of this metaphor has never been fixed. It has been stretched and redefined to fit the dominant conflicts of subsequent eras.3

19th Century

The cleavage shifted from supporting the king to the form of government, pitting monarchists (Right) against republicans (Left).3

20th Century

With the rise of industrialization and socialist movements, the spectrum was redefined again. The central political question became the "economic question."

The Left

Associated with ideologies prioritizing social and economic equality, such as socialism and communism, advocating for state intervention, public ownership, and the redistribution of wealth.4

The Right

Associated with ideologies prioritizing social hierarchy and market freedom, such as conservatism and laissez-faire capitalism, advocating for private property rights, minimal regulation, and tradition.4

This 20th-century economic definition is the one most people implicitly use today. The problem is that it attempts to compress all human political beliefs onto this single, narrow economic line.

The Critical Failure: When the Line Flattens Reality

The single-axis model is fundamentally "too simplistic and insufficient" for describing the vast variation in political beliefs.5 Its primary flaw is conflation: it incorrectly assumes that a person's views on the economy must also determine their views on social issues and personal freedom.

This conflation leads to absurd distortions. A single-axis model is incapable of distinguishing between:

An anarchist who wants to abolish all hierarchies, including the state and private property (economically Left, socially Libertarian).

A communist totalitarian who wants the state to control the entire economy and every aspect of personal life (economically Left, socially Authoritarian).

On a single line, both are simply "Left."

This distortion is most acute at the center. The model creates "the centrist distortion," where it cannot distinguish between genuine moderation and contradictory extremism.7 An individual who is, for example, extremely left-wing on economics but extremely authoritarian on social issues (a Stalinist) has their "contrasting viewpoints converge towards the center".7

This can result in a totalitarian being mapped closer to a true moderate than to their fellow extremists, rendering the entire model useless for accurate classification.

The single line of Left vs. Right is not a map; it is a flattening mechanism that erases nuance and renders key ideologies invisible. To find clarity, a new dimension is not just helpful, but necessary.

A Clearer Picture: Mapping Politics in Two Dimensions

For decades, political scientists and psychologists have recognized the limitations of the single axis and have advocated for multi-dimensional models to provide greater "scientific rigour".4 The most effective and widely accepted framework is a biaxial (two-axis) model, which separates political beliefs into two independent dimensions.

Pioneering Models

This approach is not new, though it has been refined over time.

1950s: Hans Eysenck

Psychologists like Hans Eysenck were among the first to propose two-dimensional graphs.8 He argued that political identity reflected personality, which could be measured along axes he termed "Radicalism vs. Conservatism" (the R-factor, or economic axis) and "Tender-Mindedness vs. Tough-Mindedness" (the T-factor, or social axis).8

1969: The Nolan Chart

American libertarian activist David Nolan popularized this concept with the "Nolan Chart".10 This was a critical development, as the Nolan Chart was the first popular model to explicitly plot political views along two axes: Economic Freedom and Personal Freedom.12 This design was crucial for positioning ideologies like libertarianism outside the traditional one-dimensional spectrum, correctly identifying it as a distinct philosophy rather than a variant of "right-wing" politics.10

Defining the Modern Biaxial Framework

Modern political diagnostics, including the PoliMap instrument, are built on this established biaxial foundation, which measures two separate and independent dimensions of political ideology.

1. The Economic Axis (Left – Right)

This axis is retained from the traditional spectrum but is given a more precise definition. It exclusively measures a person's attitudes toward economic policy, market control, and the allocation of resources.

The Left (Negative Polarity):

Prioritizes economic equality and collective welfare. This position favors state intervention to regulate markets, supports robust, often universal welfare programs (like Universal Basic Income, or UBI), and believes core infrastructure (like AI models) should be under public or state control [PoliMap Methodology I.C].

The Right (Positive Polarity):

Prioritizes economic freedom and individual enterprise. This position favors laissez-faire or lightly regulated markets, private property rights, fiscal conservatism (limiting public debt), and global competitiveness through deregulation.13

2. The Socio-Cultural Axis (Authoritarian – Libertarian)

This is the "missing" dimension that unlocks the map. It measures a person's attitudes toward personal freedom, tradition, social hierarchy, and the appropriate level of state authority over individual lives.5

The Authoritarian (Positive Polarity):

Prioritizes order, national security, and collective good over individual autonomy. This position believes the state is justified in repressing individual freedom (e.g., through widespread surveillance or censorship) to protect against perceived threats, and that traditional national values must be upheld by institutions.14

The Libertarian (Negative Polarity):

Prioritizes individual liberty, personal autonomy, and civil rights. This position holds freedom of speech, thought, and choice as primary values.15 It is deeply skeptical of state power, opposes state interference in personal lifestyle choices (like drug use or medical decisions), and rejects surveillance in favor of privacy [PoliMap Methodology I.C].

The most important concept of this model is independence. The two axes are not linked. A person's score on the economic axis does not predict their score on the social axis. This "decoupling" is what solves the paradoxes of the single-axis model. It allows for the full spectrum of political belief to be accurately mapped.

This two-dimensional framework is the clear, academically supported solution to the "flattening" problem. The following table summarizes the critical failure of the single-axis model and the solution provided by the biaxial map.

| Feature | Single-Axis (Left/Right) Model | Biaxial (PoliMap) Model |

|---|---|---|

| Dimensions | One dimension | Two independent dimensions |

| Core Question(s) | "What is your view on the economy?" | 1. "What is your view on the economy?" (Left/Right) 2. "What is your view on state power vs. personal freedom?" (Auth/Lib) |

| Key Flaw | Conflation & Distortion.5 Forces economic and social beliefs onto one line. | None. By separating axes, it avoids conflation. |

| Ideological Paradox | Groups contradictory ideologies (e.g., Anarchism & Stalinism) as "Left."7 | Solves the paradox. Correctly places Stalin (Auth-Left) and Anarchists (Lib-Left) in different quadrants. |

| Result | A "simplistic and insufficient"5 line that flattens reality. | A high-fidelity "map" with four distinct political quadrants. |

The Four Quadrants: A New Map for Modern Ideology

When the two axes (Economic and Social) intersect, they create a Cartesian plane with four distinct quadrants. These quadrants represent four broad "families" of political ideology, finally allowing for a level of nuance that the single line could never provide.

Quadrant I: The Authoritarian-Left (Auth-Left)

This quadrant represents ideologies that advocate for state control over both the economy and personal/social life. It is defined by the belief that the state must enforce economic equality and, simultaneously, repress individual social freedoms to maintain order, unity, and the collective will.

For decades, some researchers (particularly from the Frankfurt School) were skeptical of "left-wing authoritarianism," believing authoritarianism was an exclusively right-wing phenomenon.5 This has been demonstrably proven false by modern psychological research. A comprehensive 2021 study from Emory University, for example, successfully developed a conceptual framework to measure "authoritarianism in the political left".17 The researchers found that "left-wing authoritarians are extremely similar to authoritarians on the right" in their core "psychological characteristics".17 These shared traits include a "predisposition for liking sameness and opposing differences," "submission to people they perceive as authority figures," and "dominance and aggression towards people they disagree with".17

The study concluded they are "mirror images" of one another: right-wing authoritarians "aggressively back the established hierarchy," while left-wing authoritarians "aggressively oppose it".17 This confirms the Authoritarian-Left quadrant as a valid and measurable political and psychological space.

Quadrant II: The Authoritarian-Right (Auth-Right)

This quadrant supports a laissez-faire, capitalist, or traditionalist market economy (Economic Right) while simultaneously demanding strong state control over social and personal life (Social Authoritarian).

This ideology is defined by "blind submission to authority and the repression of individual freedom of thought and action".14 This repression is not for economic goals, but for social ones. It views certain social orders and hierarchies as "inevitable, natural, normal, or desirable" and uses state power to support them.6 This quadrant prioritizes tradition, national identity, religious law, and national security over individual liberty and cultural change.6

Quadrant III: The Libertarian-Left (Lib-Left)

This quadrant represents ideologies that are economically egalitarian (Left) but vehemently anti-state and anti-authority (Libertarian).

This is the quadrant of libertarian socialism, social anarchism, and decentralized collectivism.18 Its core tenets are "self-governance and workers' self-management".18 This position is anti-capitalist but is also anti-state. It rejects both state ownership of the economy (as in the Auth-Left) and private property.18 It seeks total personal autonomy and advocates for "actively challenging and dismantling historical power structures" [PoliMap Methodology I.C], whether those structures are governmental, corporate, or cultural.

Quadrant IV: The Libertarian-Right (Lib-Right)

This quadrant advocates for maximum individual freedom in both spheres: a free market and a free society.

This is the quadrant of classical liberalism and modern libertarianism.15 It holds "individual liberty to be the primary political value".19

It endorses a "free-market economy... based on private property rights, freedom of contract, and voluntary cooperation".20

It advocates for the "expansion of individual autonomy" and the protection of civil rights, including "freedom of speech, freedom of thought and freedom of choice".15 It believes the state has no authority to regulate personal lifestyle choices [PoliMap Methodology I.C].

| Quadrant | Economic Policy (Left/Right) | Social Policy (Auth/Lib) | Core Values |

|---|---|---|---|

| Authoritarian-Left | Left: State-controlled, collectivist economy. | Authoritarian: State-controlled society. | Equality, Order, Collective Will |

| Authoritarian-Right | Right: Free market, capitalist economy. | Authoritarian: State-controlled society. | Hierarchy, Tradition, National Security |

| Libertarian-Left | Left: Decentralized, collectivist economy. | Libertarian: Unrestricted personal freedom. | Self-Governance, Social Justice, Autonomy |

| Libertarian-Right | Right: Free market, capitalist economy. | Libertarian: Unrestricted personal freedom. | Individual Liberty, Free Markets, Minimal State |

The Measurement Problem: Why Not All "Political Compass" Tests Are Equal

Accepting the two-axis model is the first step. The second, and equally critical, step is measurement. A political map is only as good as the instrument used to place individuals upon it. Many popular online "compass" tests, while based on this biaxial model, suffer from severe methodological flaws that render their results opaque, untrustworthy, and non-replicable.

The "Black Box" Problem: Opacity and Bias

The most significant flaw in many existing tests is a complete lack of methodological transparency. They function as "black boxes": a user inputs their opinions, and a coordinate is returned, but the process of transformation is hidden.

1. Opaque, Non-Uniform Weighting:

Many tests use a large number of propositions (often 60 or more) but apply "non-uniform, non-transparent weighting factors" to them. One question may be worth 0.4 points, another 1.4, but the user is never told which is which or why. This opacity makes it impossible to validate the test's results and has led to Encyclopaedia Britannica noting that the "scientific basis for these models has frequently been questioned".13

2. Questionable Placements and Symptomatic Bias:

This "black box" methodology leads to results that are, on their face, "nonsensical".13 Academic and economic critics have pointed out the absurd placements of historical figures on some popular tests, such as placing Adolf Hitler on the economic left or classifying moderate figures like Hillary Clinton as economically "right-leaning".13 These are not mere "disagreements"; they are symptoms of a flawed, biased, or poorly calibrated model. A test whose internal logic produces such bizarre outputs is not a reliable diagnostic tool.13

3. Outdated Theoretical Foundations:

Many of these tests are built on theoretical foundations from the 1950s or 1960s9 and use "outdated questions that fail to capture contemporary political cleavages" [PoliMap Methodology, Intro]. A test that asks about 20th-century industrial policy but not 21st-century digital surveillance is a historical artifact, not a modern instrument.

The PoliMap Solution: A Commitment to Transparency

A trustworthy diagnostic tool cannot be a "black box." The PoliMap instrument was designed specifically to solve these methodological failures through an absolute commitment to transparency.

- Contrast 1: Where other tests are opaque, PoliMap's methodology is "completely transparent" [PoliMap "About"].

- Contrast 2: Where other tests use hidden, non-uniform weights, PoliMap mandates that "Every proposition is uniformly weighted" [PoliMap "About"].

- Contrast 3: Where other tests hide their calculations, PoliMap's "scoring algorithm is mathematically explicit and publicly documented" [PoliMap "About", Methodology IV].

A two-axis model is only as good as its methodology. An accurate test must be transparent, replicable, and methodologically sound.

The New Fault Lines: What Defines Politics in the 21st Century?

A political test is not just a mathematical model; it is a snapshot of contemporary conflicts. To be accurate, a test must ask questions that reflect the actual "fault lines" of the current political landscape. A test that fails to measure 21st-century cleavages will fundamentally misclassify a 21st-century user.

The PoliMap instrument is built around these "new cleavages"—the high-stakes trade-offs that define modern political discourse [PoliMap Methodology I.C].

New Cleavage 1: Digital Governance (AI & Surveillance)

The digital realm has created entirely new battlegrounds for state power and personal liberty.

Surveillance vs. Privacy: This is the new face of the Authoritarian/Libertarian conflict. Does national security justify "widespread, digital surveillance of all public communications"?21 This is the central question of "digital authoritarianism," which sees states aggressively using technology to monitor and control populations.22 Or is digital privacy a fundamental human right to be protected from both state and corporate power?24

AI Governance: Artificial Intelligence presents a new cleavage on both axes.

- Economic (Left/Right): "Core AI technologies... should be placed under public ownership or state control" [PoliMap Prop E1]. This is a modern reframing of the classic Left/Right debate over the "means of production".25

- Social (Auth/Lib): The governance of AI has become a profound cultural battle. The conflict is between those who fear AI models are being trained with "ideological biases" and "social agendas" (like DEI or "woke" concepts) at the "cost of accuracy"26, and those who believe AI must be regulated to strengthen worker protections and prevent algorithmic discrimination.27

New Cleavage 2: Globalization vs. National Sovereignty

The 20th-century consensus on globalization has shattered, replaced by "globalization fatigue" [PoliMap Methodology I.C]. The new conflict is between proponents of global integration and proponents of national sovereignty.28

The "Political Trilemma": Harvard economist Dani Rodrik famously argued that it is "impossible to have full national sovereignty, democracy, and globalization simultaneously".29 This "political trilemma" forces a choice.29

PoliMap Relevance: This is precisely the trade-off measured by PoliMap's proposition on protectionism [Prop E8]. The proposition "Protecting domestic strategic industries through tariffs and subsidies is necessary for national security" forces the user to choose between the market efficiency of globalization and the security of national sovereignty.30

New Cleavage 3: Identity Politics vs. Civic Universalism

Perhaps the most dominant socio-cultural cleavage of our time is the conflict over identity. "Identity politics" is defined as politics based on a particular group identity, such as race, ethnicity, gender, or religion.31

The Conflict: This phenomenon exists "on both sides of the political spectrum".32 It frames political claims as a "tool... in a larger context of inequality or injustice"31 and can be "solidaristic" (focusing on an ingroup) or "oppositional" ("us versus them").34

PoliMap Relevance: This is a high-impact, polarizing conflict that a modern test must measure. PoliMap's Prop S4 ("Societal progress requires actively challenging and dismantling historical power structures based on race and gender") is specifically designed to gauge a respondent's position on this central modern cleavage [PoliMap Methodology I.C].

An accurate political map must include these new landmarks. A test that relies on legacy debates while ignoring AI, digital surveillance, globalization fatigue, and identity politics is a historical document, not a valid diagnostic tool.

The Science of the "Strongly Agree": How a Valid Test Is Built

Finally, building a high-fidelity political instrument is not just a matter of political science; it is a matter of psychometrics—the science of psychological measurement. The design of the test, particularly its response scale, is as important as the content of its questions. A poorly designed scale will introduce noise, bias, and measurement error, invalidating the results.

The "Fence-Sitting" Problem (Why a 5-Point Scale Fails)

Most online surveys use a 5-point Likert scale (e.g., Strongly Disagree, Disagree, Neutral, Agree, Strongly Agree).35 For an ideological diagnostic, this neutral midpoint is a psychometric trap.

- It Encourages "Fence-Sitting": This neutral option is "problematic" because it attracts respondents who do have a "latent preference" or slight directional leaning but are "unwilling to commit" to a stance.36

- It Invites "Satisficing": A neutral option is also an easy cognitive shortcut for unmotivated respondents. This behavior, known as "satisficing," occurs when a respondent skips the hard work of evaluating a proposition and simply picks the middle option to get through the survey.37

In both cases, the result is bad data. The neutral option "reduces the measurable variance" in the dataset and masks the very ideological signal the test is designed to detect [PoliMap Methodology II.A].

PoliMap's Solution: The 4-Point Forced-Choice Scale

The PoliMap instrument deliberately removes the neutral option, utilizing a 4-point forced-choice scale (Strongly Disagree, Somewhat disagree, Somewhat agree, Strongly Agree) [PoliMap "About", Methodology II.A].

The Justification: This design is "methodologically superior for this instrument" [PoliMap Methodology II.A]. It "forces directionality"36, requiring the respondent to express some directional preference, even if slight.

The Result: This design "maximizes the ideological signal" [PoliMap Methodology II.A]. Research on forced-choice formats confirms they can result in "better-quality data"38 and are less susceptible to specific response biases like acquiescence.39 It is a rigorous, deliberate design choice to improve accuracy.

"Don't Know" Is Not "Neutral": The Pitfall of Ambiguity

A separate but related issue is the "Don't Know" (DK) option. It is a profound methodological error to treat "Don't Know" and "Neutral" as the same thing.

- A "Neutral" response implies a person has weighed the options and their position is perfectly balanced at the center (a '0' on the axis).

- A "Don't Know" response indicates a lack of knowledge or information.37 The respondent has no position.

As the PoliMap methodology correctly identifies, scoring a "Don't Know" response as a '0' (neutral) "introduces measurement error and misclassification". It falsely equates two "fundamentally different psychological states": a lack of information and genuine ideological centrism.

PoliMap's Solution: Exclude 'DK' from Scoring

The only psychometrically valid approach for a diagnostic test is the one implemented by PoliMap: "Don't Know" responses, if collected, are "excluded from the summation of the Axis Raw Score".

This ensures that the "final calculated position reflects only the opinions a respondent actively holds". This protocol "maintain[s] the psychometric integrity necessary for reliable spatial placement."

This rigorous attention to test design—the 4-point scale, the uniform weighting, and the correct handling of ambiguity—is what separates a high-fidelity scientific instrument from a low-fidelity online quiz.

Finding Your True Political Coordinates

The journey to political self-understanding begins with discarding broken tools. This analysis has demonstrated that:

- 1The traditional Left/Right axis is an outdated 18th-century metaphor2 that "flattens" and "distorts" modern political belief.7

- 2The two-axis model (Economic Left/Right and Social Authoritarian/Libertarian) is the academically supported standard5, revealing four distinct and meaningful political quadrants.14

- 3Many online "compass" tests are flawed "black boxes" that use opaque, non-transparent, and outdated methodologies, leading to questionable results.13

- 4A truly accurate instrument must be built on two non-negotiable foundations: Contemporary Relevance (asking about AI, globalization, and identity)22 and Methodological Rigor (transparent weighting and a forced-choice scale that correctly handles neutrality).37

The PoliMap instrument was designed from the ground up to be the solution to these problems. It is not just another quiz. It is a modern, 20-item diagnostic instrument built for the 21st century.

Methodologically Transparent

With a "mathematically explicit" and publicly documented algorithm [PoliMap "About", Methodology IV.C].

Contemporarily Relevant

With propositions precision-engineered to measure the political fault lines of the modern world, including digital governance, AI infrastructure, and identity politics [PoliMap "About"].

Psychometrically Rigorous

Using a 4-point forced-choice scale designed to maximize accuracy and eliminate the "fence-sitting" and "satisficing" biases that plague other tests [PoliMap "About"].

The goal of this instrument is to provide individuals with an "accurate, transparent, and methodologically rigorous assessment" of their political ideology [PoliMap "About"]. The theory has been explained, the map has been drawn, and the science has been validated. The final step is discovery.

Works Cited

- Political Left and Right: Our Hands-On Logic, accessed November 7, 2025

- What to Know About the Origins of 'Left' and 'Right' in Politics, From the French Revolution to the 2020 Presidential Race — Time Magazine, accessed November 7, 2025

- Left–right political spectrum — Wikipedia, accessed November 7, 2025

- Political spectrum | Definition, Chart, Examples, & Left Versus Right — Britannica, accessed November 7, 2025

- Political spectrum — Wikipedia, accessed November 7, 2025

- Right-wing politics — Wikipedia, accessed November 7, 2025

- The Three-Axis Political Compass. Economics, domestic policy, and foreign… — The Outsider | Medium, accessed November 7, 2025

- Political Compass — The Decision Lab, accessed November 7, 2025

- The Political Compass Test and the Death of Politics — Columbia Political Review, accessed November 7, 2025

- Nolan Chart — Wikipedia, accessed November 7, 2025

- The Nolan Chart — Bubble Enterprises, accessed November 7, 2025

- Political Views in Three Dimensions — FEE.org, accessed November 7, 2025

- The Political Compass — Wikipedia, accessed November 7, 2025

- Authoritarianism | Definition, History, Examples, & Facts — Britannica, accessed November 7, 2025

- Libertarianism — Wikipedia, accessed November 7, 2025

- Libertarianism — Wikipedia, accessed November 7, 2025

- Left-wing authoritarians share key psychological traits with far right, Emory study finds, accessed November 7, 2025

- Libertarian socialism — Wikipedia, accessed November 7, 2025

- Libertarianism | Definition, Philosophy, Examples, History, & Facts — Britannica, accessed November 7, 2025

- Libertarianism — Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy, accessed November 7, 2025

- Politics of Digital Surveillance, National Security and Privacy, accessed November 7, 2025

- Digital Privacy Rights Resource — GW Law - The George Washington University, accessed November 7, 2025

- Big Question: How Does Digital Privacy Matter for Democracy and its Advocates?, accessed November 7, 2025

- How surveillance changes people's behavior — Harvard Magazine, accessed November 7, 2025

- Co-Governance and the Future of AI Regulation — Harvard Law Review, accessed November 7, 2025

- Preventing Woke AI in the Federal Government — The White House, accessed November 7, 2025

- Artificial Intelligence 2025 Legislation — National Conference of State Legislatures, accessed November 7, 2025

- National Sovereignty Vs. Globalization — Academicus International Scientific Journal, accessed November 7, 2025

- Democracy beyond the nation-state — Brookings Institution, accessed November 7, 2025

- Sovereignty of what and for whom? The political mobilisation of sovereignty claims by the Italian Lega and Fratelli d'Italia — PubMed Central, accessed November 7, 2025

- Identity politics — Wikipedia, accessed November 7, 2025

- How America's identity politics went from inclusion to division — The Guardian, accessed November 7, 2025

- Identity Politics in Context — Gallup News, accessed November 7, 2025

- Understanding Identity Politics: Strategies for Party Formation and Growth — FSI, accessed November 7, 2025

- Likert Scale vs. Forced Choice (aka Normative vs. Ipsative) for Effective Employee Selection, accessed November 7, 2025

- Does Removing the Neutral Response Option Affect Rating Behavior? — MeasuringU, accessed November 7, 2025

- Full article: Effects of objective and perceived burden on response quality in web surveys, accessed November 7, 2025

- (PDF) Not Liking the Likert? A Rasch Analysis of Forced-choice Format and Usefulness in Survey Design — ResearchGate, accessed November 7, 2025

- Controlling for Response Biases in Self-Report Scales: Forced-Choice vs. Psychometric Modeling of Likert Items — PubMed, accessed November 7, 2025

- Dismissing "don't know" responses to perceived risk survey items threatens the validity of theoretical and empirical behavior change research — PMC - PubMed Central, accessed November 7, 2025